CONCEPT

COLLABORATING WITH LACQUER

Each time I interact with the lacquer, it responds, and I, in turn, respond to its changes — lacquer-based creation is a process that takes place through a back-and-forth exchange, much like a dialogue. I see my relationship with this material as a “collaborative creation” with lacquer. While oil painting is a medium that can relatively faithfully output one’s intentions, lacquer presents me with reactions that cannot be controlled, such as changes in color and the layers of the coating. In this way, I am often swept up in the changes and responses that the material brings. However, I find this process very comforting and precious. I do not view lacquer as merely a material; rather, I perceive it as having will, as though it possesses a personality of its own, independent and self-sustaining. What is it like to interact with a material that, unlike human beings, cannot communicate in words? How do I respond to the subtle reactions lacquer communicates?

While there are specific approaches, such as exploring the relationship between polishing, color changes, and the depiction, I also attempt to become closer to the material, lowering myself from the privileged “human” standpoint to understand it better. Finding meaning in the exchanges that occur through scars is one such example. These acts might be akin to a kind of spell, but I treasure them to preserve the sensation of hearing lacquer speak, even if just for a moment. As I continue to build this relationship, my themes of creation have expanded to encompass connections with non-human entities and dialogues with nature. Through lacquer, my awareness of creation itself is reshaped, and the very act of considering my connection with the world through lacquer becomes my “collaborative creation.”

Wood and Blood

Lacquer is a material that has been intertwined with human life and culture since ancient times, dating back over 9,000 years. It is the sap extracted from the Urushi tree, which grows in East and Southeast Asia. The sap is collected by making cuts in mature trees, and it takes about six months to extract it without killing the tree, eventually cutting it down at the end of the process. This method is known as “killing scraping” and is often likened to an act of taking life. Some lacquer gatherers describe this work as heartbreaking. Additionally, the sap itself naturally solidifies to seal the tree’s wounds, and if we were to compare it to humans, it can be seen as the blood that forms scabs. Afterward, the “Urushi” as a plant transforms into lacquer, used as a paint or adhesive.

Interestingly, even after it is processed into a material, lacquer does not cease to exhibit signs of life. For example, during the drying process, which progresses through enzymatic reactions, the quality and coloration of the coating change depending on the environment. Moreover, even after completion, lacquer continues to evolve, gradually becoming more transparent and hardening as if the tree were still growing. As a result, the color becomes more vibrant, and the coating strengthens. I have witnessed these organic reactions in lacquer many times throughout the creative process, and gradually, I could no longer view lacquer as just a plant. This is why I cannot desire to fully control lacquer, nor can I treat it carelessly as a “thing” without a spirit. This feeling seems to be shared among those who engage with lacquer. If we were to call this “Lacquer View,” I believe it is a sensibility that is naturally absorbed into the body and mind through deep involvement with the culture, growing environment, and the actual process of working with lacquer.

— A Living Material

The sense of life inherent in lacquer emanates a presence as if it were a living being, through its organic reactions and changes. This characteristic fosters an awareness that treats lacquer not merely as a material but as a kind of partner.

— Lacquer Philosophy

The unique sensibility and philosophy shared by those who work closely with lacquer is termed “Lacquer Philosophy.” This perspective is nurtured through the cultural background of lacquer, its natural environment, and experiences in the creative process, and it is considered an important viewpoint in understanding lacquer.

Mediator

Recognizing lacquer as a co-creator has expanded my focus to include symbiosis with non-human and other species. The lacquer tree, with its fruit covered by a hard resin, is artificially cultivated, and the culture of lacquer as a paint has been built through human intervention. In this way, lacquer is both artificial, requiring human intervention, and a natural entity that continues to undergo spontaneous changes even after it becomes a paint. Lacquer plays the role of a mediator between nature and humanity.

My interests have broadened beyond living organisms to include inanimate entities like lacquer—natural phenomena such as earth and air, as well as non-human entities. The web of ecosystems and cultures that extends beyond human society is closely tied to contemporary issues such as rural depopulation and disasters. I am increasingly aware that our daily lives are supported by these interconnected systems. Furthermore, my interest has expanded to include myths and legends that bridge the past and the present, woven through human interaction with nature. Just as the ecology of lacquer and its techniques are born from long relationships with land and environment, storytelling also emerges through these connections, accumulating over time. The spread of vegetation and culture is influenced by human activities, but it is not bound by the human-made boundaries of nations. Reflecting on the complex, organic, and ever-evolving traces and perspectives of past people, I seek to find connections to the present.

— Lacquer as Both Culture and Plant

Lacquer functions as a mediator between nature and humans, and between the past and present. Its dual nature serves as a catalyst, expanding my interests in a chain-like manner.

— The Web of Ecosystems and Culture

Through lacquer, my focus has shifted toward the symbiosis with non-human entities, and the web of ecosystems, extending my interest to the connections between our lives and the world beyond human society.

—The Growing Range of Plants, the Continuity of Traditions and the Present

The growth range of lacquer trees stretches from the northeastern tip of Japan’s Tohoku region to South Korea, southern China, Myanmar, and the southernmost parts of Vietnam. Just as they easily cross borders, stories that link the past and the present, as found in legends and myths, also spread organically, offering a chance to reconsider the relationship between nature and humanity.

Evolution

URUSHI LACQUER PAINTING

Lacquer painting, known as urushie (漆絵) or shitsuga (漆画) in Japanese, is a form of painting that developed in East and Southeast Asia. It originated in Vietnam in the early 20th century and later influenced artistic expressions in China in the latter half of the century. In both Vietnam and China, lacquer painting is recognized as a distinct genre within painting. In contrast, in Japan, where lacquer has traditionally been closely associated with craft, lacquer-based two-dimensional works primarily evolved within the framework of craft rather than as paintings. Regardless of the country, the emergence of lacquer painting was shaped by the encounter between Western artistic concepts introduced in modern times and the traditional craft culture of indigenous lacquer arts. Lacquer painting is a relatively new artistic expression that has emerged from the intersection of different cultures within the contemporary context of East and Southeast Asia.

— The Lacquer Cultural Sphere and Europe

The development of lacquer painting across regions was influenced not only by interactions among East and Southeast Asian countries such as Vietnam, China, and Japan but also by the transmission of artistic movements through France, which played a central role in Japonisme and the Art Deco movement. The exchange of people, techniques, and ideas also played a significant role. The evolution of lacquer painting reflects a complex interplay of cultures, technologies, and systems that transcended national borders, resulting in a rich and dynamic fusion of artistic traditions.

The Birth and Cultural Context of Lacquer Painting: Vietnam, China, and Japan

Lacquer painting emerged in Vietnam in the 1930s, during the period of French colonial rule. It is said to have originated in the lacquer course at an art school established to promote industrial arts, where French painters and teachers such as Joseph Inguimberty and Alix Aymé collaborated with Vietnamese lacquer craftsmen to develop lacquer painting (Sơn mài). From this movement, figures such as Nguyễn Gia Trí, a leading artist in Vietnamese lacquer painting, emerged. Although the birth of lacquer painting was influenced by the colonial context, it has since established itself as a modern painting genre representing the national identity of Vietnam.

In China, during the 1930s, exchanges with Japanese lacquer artists and studies in France were actively pursued, leading to the creation of decorative lacquer panels by artists such as Li Zhiqing, Shen Fuwen, and Lei Guiyuan. However, it was only after the Vietnamese lacquer painting exhibitions were held in Shanghai and Beijing in the 1960s that lacquer painting was seriously pursued as a form of painting. Led by Qiao Shiguang, painters with backgrounds in oil painting, traditional Chinese painting, and printmaking, as well as lacquer artists who actively engaged in exchanges with Vietnam, sought to establish lacquer painting (qī huà) as a new genre of painting.

In contrast, in Japan, lacquer painting has been closely associated with craft, and the notion that “lacquer painting does not exist in Japan” has been widely circulated. However, this statement refers only to lacquer painting as a recognized painting category. Before the modern classification of art took hold, various works demonstrated a fusion of lacquer craftsmanship and painting. Examples include the maki-e panel created by Shibata Zeshin for the 1873 Vienna World Exposition, decorative wall panels by Yamazaki Kakutarō in the 1930s, and lacquer panels developed by his disciple Takahashi Setsurō in the 1950s, which refined this style. While these works are generally classified within the field of craft, they also possess strong pictorial elements as flat works. Furthermore, artists who sought to pursue lacquer painting in a more explicitly pictorial direction did exist. Examples include the Western-style painter Yokoi Kōzō, who originally began his career in lacquer painting, Masao Matsuoka, who organized a lacquer painting group, and Takezo Sato, a watercolorist who was active in the UK. However, their works were not considered fully within the domain of craft, nor were they recognized as mainstream painting, leading to their marginalization. As a result, their contributions were overlooked by both fields, and lacquer painting as a pictorial form that once existed in Japan faded into obscurity within art history.

— Vietnam

During the French colonial period in the 1930s, French painters and Vietnamese lacquer craftsmen collaborated in the lacquer course at an art school to develop lacquer painting (Sơn mài). Today, it has been established as a form of modern painting representing the nation and has become an art form that reflects cultural identity.

— China

In the 1930s, following exchanges with Japanese lacquer artists and studies in France, decorative lacquer panels began to be produced. Later, in the 1960s, influenced by Vietnamese lacquer painting exhibitions, efforts were made to establish it as a new genre of painting.

— Japan

“Lacquer painting” has primarily been treated as a craft. In Japan, there is a prevailing impression that pictorial lacquer painting has rarely been practiced, yet there were painters who once engaged in lacquer painting. They attempted to transcend the boundary between painting and craft, but their work was overlooked as an intermediate existence between the two fields.

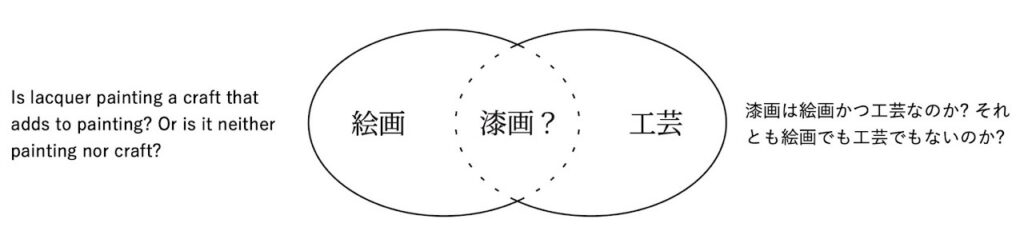

What is Lacquer Painting? /Painting and Craft

However, if we examine these claims more closely, we realize that the meanings associated with terms like “painterly” and “craft-like” vary depending on one’s perspective. For example, both painters and craftsmen use the word “plane,” but their interpretations differ. For a painter, a plane is closely tied to the concept of “frontal composition,” while for a craftsman, a plane is continuous with three-dimensionality and is perceived in relation to form, with an emphasis on the sense of “surface.” As a result, a work painted on a freestanding screen is considered three-dimensional (since it can be viewed from all sides) in a painterly sense, while in a craft context, it is classified as a plane (due to its large, smooth surface), creating a contradiction.

Another crucial issue lies in the question, “Why treat lacquer like paint?” This question implies a concern that treating lacquer in a painterly manner obscures its materiality and presence. When lacquer’s unique properties are diminished and it is reduced to compositional elements like lines and color fields, it may be seen as no longer a “lacquer painting” — or rather, as evidence that “lacquer is not meant for painting.”

If lacquer painting was born from the encounter between Western painting and traditional lacquer art, can it be considered a new form of expression that incorporates elements of both painting and craft? As the history of lacquer painting in Japan demonstrates, affirming this question is not so simple. In my own creative process, I have often faced the question, “Is this painting or craft?” and have received critiques such as “too painterly,” “too decorative,” or “why treat lacquer like paint?” Because lacquer painting emerged as a hybrid of painting and craft, it often belongs to neither and is regarded as something that is “neither painting nor craft.”

Seeking to Create the Reciprocity of Image and Material

The positioning of lacquer painting in the classification of art remains suspended between painting and craft. However, both the pictorial lacquer paintings and the craft-based lacquer paintings, when reconsidered from the perspective of the “painting” itself, reveal that the “body” of a painting is essentially an object. Yet, it is only when the object ceases to be perceived as an object that the painting emerges as an image through our human act of “seeing” and is recognized by our brain. This cannot be explained solely through elements associated with painting and craft, such as flatness or ornamentality. The image is always intrinsically tied to material, and it can be said that the potential for the image to emerge exists within all materials across the boundaries of painting and craft.

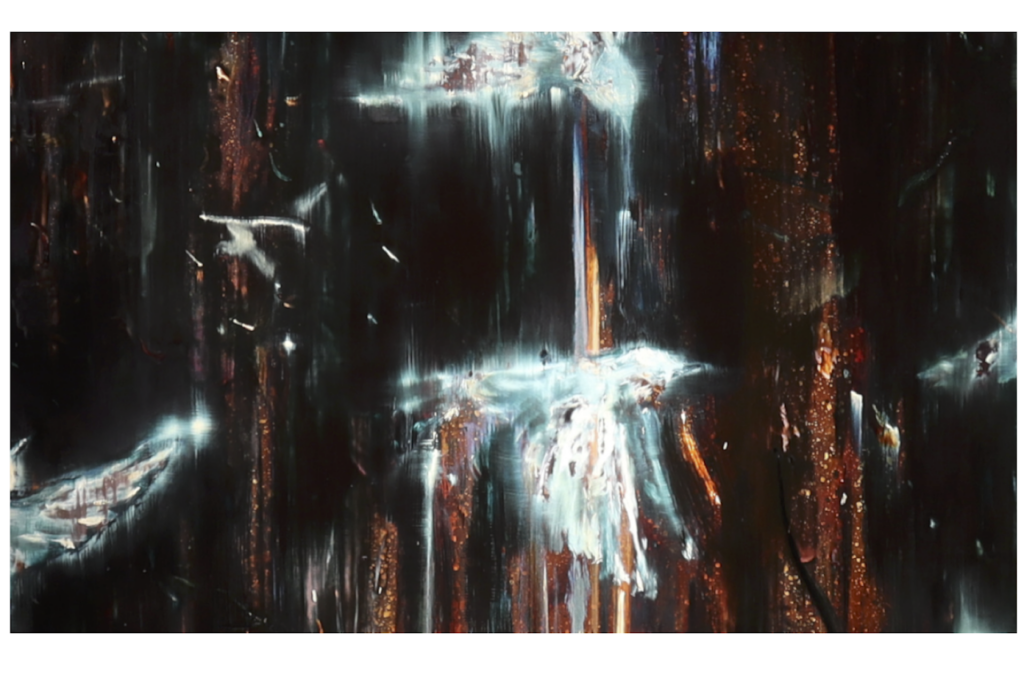

In light of this, I am seeking to create a dynamic reciprocity where image and material continuously alternate on the surface of the lacquer painting. The images provided in the works are somewhat abstract. I do not concede all to the illusion of painting; I do not hide the lacquer’s true nature. At the same time, I do not entirely leave everything to lacquer, turning it into pure abstraction or phenomena. I am always conscious of the materiality of lacquer and the presence of the image that can be discovered beneath its thin lacquer coating. By exploring the duality inherent in painting, I hope to reconsider and reconnect the divided realms of painting and craft, providing new insights into their coexistence.

— Reciprocity Between Material and Image

Rather than allowing the painted image to obscure the presence of lacquer, I hoping to achieve to create a surface where the two continuously alternate before the viewer’s eyes. My goal is for lacquer to remain lacquer while coexisting with imagery. This duality inherent in painting becomes even more vividly apparent through the materiality of lacquer.

techniques

The Process of Lacquer Painting

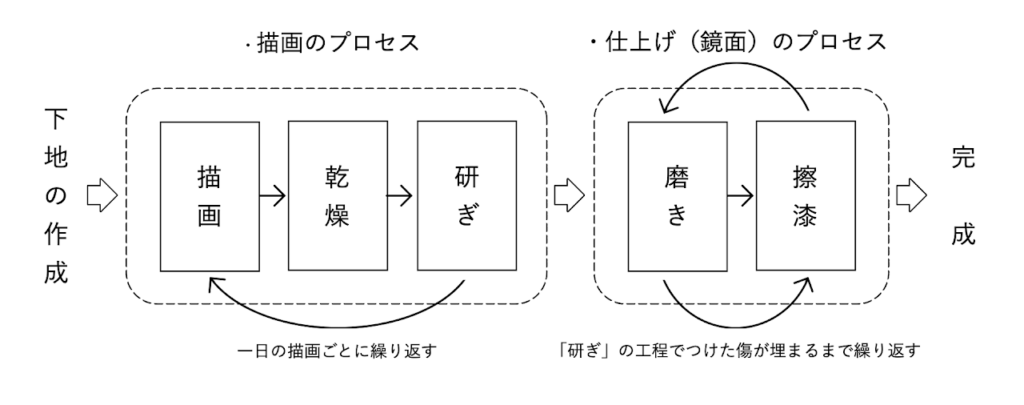

The creation of a lacquer painting progresses through multiple stages. The basic cycle involves first preparing a base layer by mixing diatomaceous earth with lacquer, then applying the imagery, and finally completing the finishing process. Once the lacquer dries, a sanding process is essential to enhance adhesion for the next layer. In the final polishing stage, lacquer is rubbed into microscopic scratches, then wiped away, and the surface is gradually polished using increasingly fine whetstones in a repetitive process.

Through these steps, the time spent sanding the lacquer surface with water and whetstones and polishing it with the palm of my hand far exceeds the time spent painting with a brush. This continuous cycle of sanding and polishing feels as if it extends my bodily perception into the time of lacquer itself. The prolonged engagement with this process has also served as a gateway to a heightened awareness of the presence of nature.

The Refining Tree Sap and Types of LacquerProcess of Lacquer Painting

The raw lacquer sap collected through urushi tapping is first gathered in wooden barrels. Over time, fermentation progresses, causing bubbles to rise and push against the lid, releasing a sweet and sour aroma. This fermentation is triggered by anaerobic bacteria living in the tree bark (igosō) that mix into the sap during collection. The sap is then transported to a lacquer wholesaler for refinement. Traditionally, this refining process, known as Nayashi and Kurome, was carried out by hand under the sun on clear days. By stirring, applying heat, and evaporating moisture, the lacquer’s components are evenly blended, resulting in a beautiful amber hue and a high-quality coating.

Various colors of lacquer are created based on this amber-toned suki-urushi (transparent lacquer). When pigments are added, it becomes iro-urushi (colored lacquer), which can be either transparent or opaque, sometimes incorporating metal powders. The commonly seen red lacquer is made by adding pigments like bengara (red iron oxide), while black lacquer is uniquely developed through a reaction with iron.

— Nayashi & Kurome

The process of stirring lacquer to evenly blend its separated components is called Nayashi (stirring), while the process of heating and dehydrating the lacquer is known as Kurome (darkening).

—Lacquer Refinement

The freshly harvested, unprocessed lacquer sap is referred to as aramisho-urushi (raw sap lacquer). When impurities such as wood debris and dust are filtered out, it becomes rojō-namashi-urushi (filtered raw lacquer). Through further refining, it is transformed into seisei-namashi-urushi (refined raw lacquer). This milky white lacquer is then subjected to the Nayashi and Kurome processes, further refining it into a semi-transparent, amber-colored suki-urushi (transparent lacquer).

Aging of Colors and the Hardening Mechanism

The drying of lacquer progresses through an enzymatic reaction. The reason for adjusting the environment to be warm and humid is to enhance the activity of these enzymes. In optimal conditions, lacquer becomes dry to the touch after being left overnight (approximately six hours). However, interestingly, the enzymes continue to react beyond this point, further solidifying and strengthening the lacquered surface. Once hardened, lacquer becomes resistant even to acids, which is why it has been used as an adhesive since ancient times.

In parallel with hardening, the initially brownish lacquer coating gradually becomes more transparent over the years. While it never becomes completely clear, the brown tint fades, allowing the pigments to reveal their true colors more vividly. Lacquer is not an inorganic material; even after being shaped into an artwork, it continues a slow transformation, much like the steady growth of a tree.

— Urushiol and Laccase

The hardening of lacquer occurs through a chemical reaction in which an enzyme called laccase, present in the lacquer, reacts with moisture in the air. This reaction polymerizes a special component called urushiol over time. Unlike drying through the evaporation of moisture, lacquer hardens through an enzymatic chemical reaction. For this process to take place, the optimal conditions require a temperature of around 25°C and a humidity level of approximately 75%.

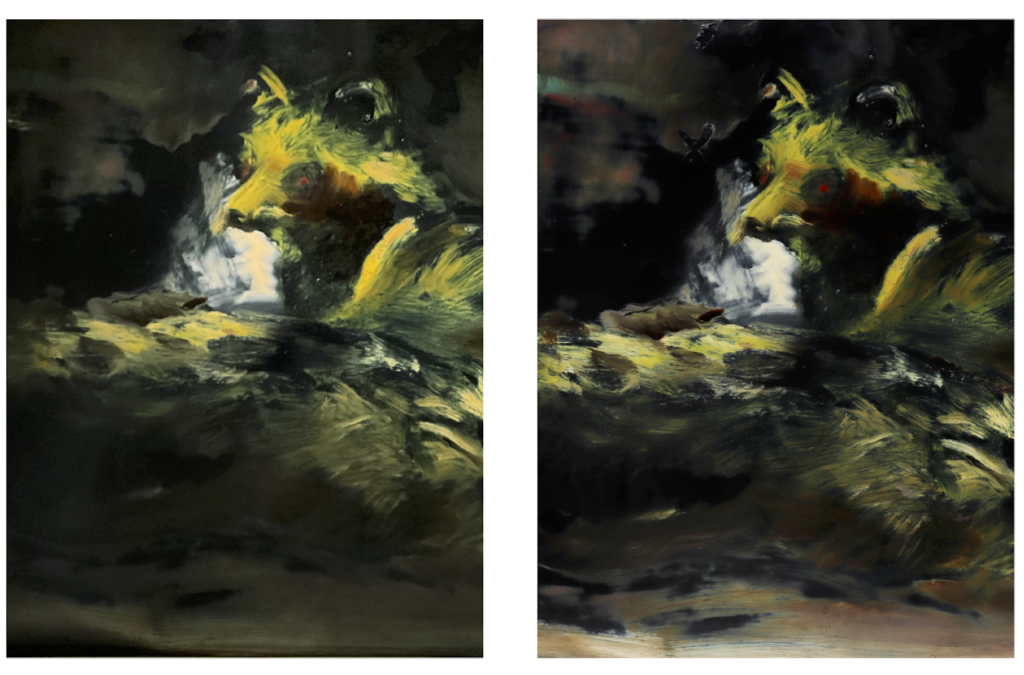

Lacquer Film Drying

The left image shows the state immediately after painting, while the right image shows the state after approximately six hours.

After drying, the lacquer’s brownish tint becomes more prominent over the pigments, darkening the overall color. The degree of color change varies depending on environmental conditions and the composition of the lacquer.

Aging Process

The left image shows the artwork immediately after completion, while the right image shows its appearance after two years.

The bluish-green streak in the upper left corner and the red coloration of the tanuki’s eyes have become more vivid over time.

Lacquer Layers

Broadly, the layers can be divided as follows: the white bird layer at the forefront, the black lacquer layer, the brown translucent lacquer layer, the dotted layer, and the base layer.

Through polishing and the use of translucent lacquer, approximately five layers beneath the surface are visible.